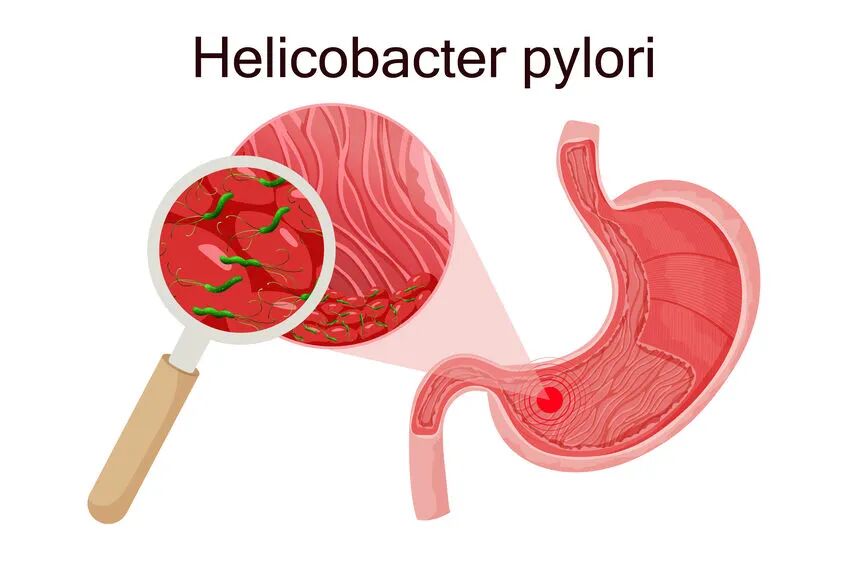

Helicobacter pylori, more commonly known as H. pylori, is a spiral-shaped bacterium that lives in the stomach. Despite how unfamiliar the name may sound, it is one of the most widespread infections in the world. In some regions (including China) more than half the population carries it- often without knowing. While many people live with H. pylori peacefully, the bacterium is also the leading cause of peptic ulcers and a major risk factor for certain types of stomach cancer. Understanding what it is, how it spreads, and when it needs treatment can make a meaningful difference to long-term health and daily quality of life.

How H. pylori Spreads

H. pylori usually spreads through direct contact, most commonly in childhood. It can be passed through saliva, contaminated water, shared eating utensils, and close household contact. Crowded living conditions and limited access to clean water historically increased transmission rates, which is why older generations tend to have higher infection rates than children today.

Once it enters the stomach, H. pylori has a unique ability to survive the acidic environment that would normally kill other bacteria. It burrows into the stomach lining and produces substances that weaken the protective mucus layer. This can cause inflammation (known as gastritis) and, in some people, lead to ulcers in the stomach or the first part of the small intestine.

Symptoms and Complications

Most people with H. pylori feel completely well. The infection often causes no symptoms at all. However, when symptoms do occur, they may include burning stomach pain, bloating, nausea, loss of appetite, or frequent burping. Because these symptoms are nonspecific, they are often mistaken for general “stomach issues”. Because these symptoms overlap so closely with acid reflux, indigestion, and functional dyspepsia, H. pylori infections are often initially misdiagnosed as GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease), delaying appropriate testing and treatment.

The above complications may further contribute to:

Peptic ulcers: open sores in the stomach or duodenum

Chronic gastritis: ongoing inflammation of the stomach lining

Stomach cancer: particularly gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma

Fortunately, only a small percentage of people with H. pylori will go on to develop stomach cancer, but even the milder symptoms of H. pylori can be uncomfortable and needlessly affect quality of life when simple and effective treatment is available.

Diagnosis

Doctors have several ways to detect H. pylori. The most common are the urea breath test, stool antigen test, and blood antibody test. Breath and stool tests are preferred because they can show whether the infection is active, not just a past exposure. In some cases- especially if symptoms are severe or persistent- doctors may test for H. pylori during an endoscopy.

Since many cases of H.pylori are not producing symptoms, you can ask your doctor to add the test to your annual health check-up. It is also often advised that those caring for young infants and children (e.g. grandparents or ayi) be tested so that H. pylori is not spread further to younger generations.

Treatment

If H. pylori is causing symptoms or complications, treatment is straightforward: a combination of antibiotics and acid-reducing medication for 10–14 days. Because antibiotic resistance is increasing worldwide, it’s crucial to take medications exactly as prescribed and to complete the full course.

Prevention and Outlook

Good hygiene, especially handwashing and safe food and water practices, remains the best prevention. If H.pylori is detected, treatment can improve quality of life, reduce the need for long-term use of antacids or medicines to inhibit stomach acid production, and prevent the spread of the bacteria to other family members. After successful treatment, most people experience complete healing of ulcers and a significant reduction in stomach symptoms. In short, while H. pylori is common, it is also very manageable with the right care.

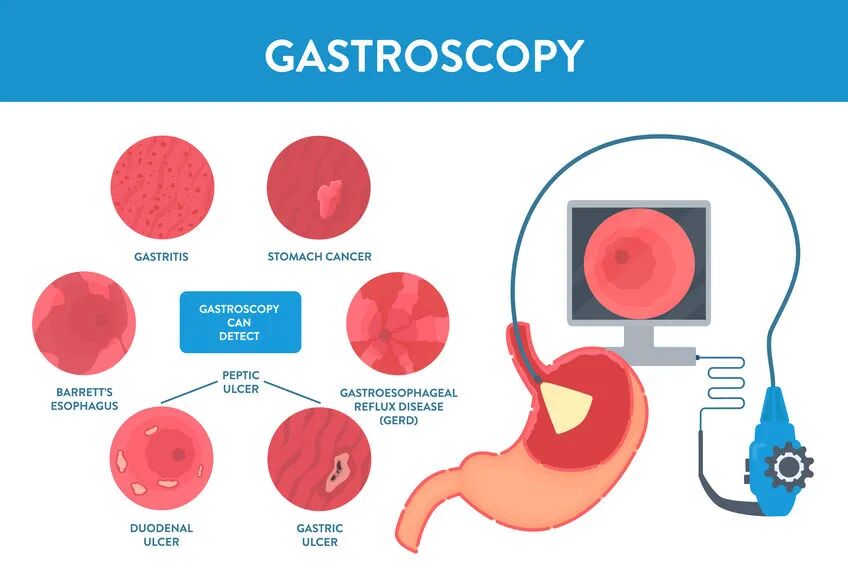

When is Endoscopy Recommended?

Routine upper endoscopy (gastroscopy) is recommended for certain groups, even for people without obvious H. pylori infection or significant symptoms. Current Chinese screening guidelines (2024) suggest starting routine endoscopy screenings at 45 years of age, or at 40 years old for people with H. pylori infection, a family history of gastric cancer, other risk factors such as chronic atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, or lifestyle risk factors (e.g., heavy smoking or high-salt diet).

By following these age- and risk-based recommendations, endoscopic screening can catch precancerous changes earlier, even in those without symptoms, thus greatly improving opportunities for timely intervention.